Seated in her sunny living room, Frances Holliday Alford asks lots of questions before talking about herself and her work. When she does, it’s clear that making art and the process of finding a path to art making affect her deeply. She is inquisitive and insightful—and always on the lookout to extend her community.

Piecing a Narrative

Alford is an internationally known fiber artist who makes her home in Grafton, a few blocks from where she spent her childhood summers visiting her grandparents’ home. She has exhibited widely, including at the International Quilt Festival in Houston every year since 1999, and in Austin, Chicago, Grafton, and Long Beach. Internationally she has had quilt shows in in Lyon, France; The Hague, Netherlands; Costa Rica; and Kazakhstan. This year she will exhibit for the first time at the Festival of Quilts in England (the largest quilting festival in Europe) as well as for the first time at the Bojagi Forum in Suwon, South Korea.

Describing Alford as a quilt artist might seem surprising given her broad range of interests, but consider the world of contemporary quilts, fiber arts, surface design, and the community of makers, and it’s possible to begin to understand the richness Alford finds in that world.

Describing Alford as a quilt artist might seem surprising given her broad range of interests, but consider the world of contemporary quilts, fiber arts, surface design, and the community of makers, and it’s possible to begin to understand the richness Alford finds in that world.

That said, she doesn’t limit her investigations to quilting when inspiration arises.

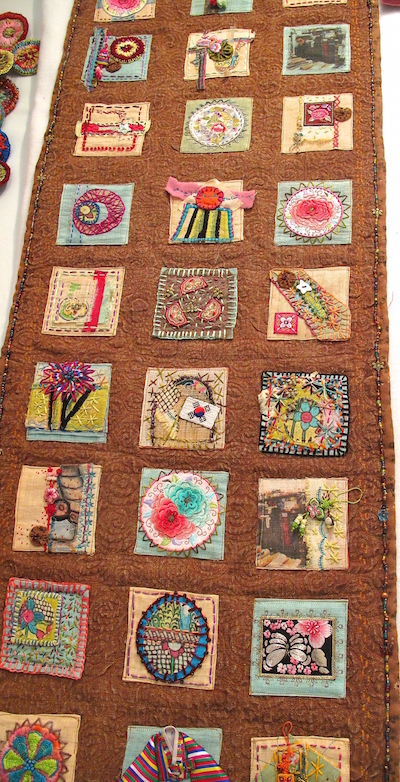

Vibrant colors and complex compositions supply drama for Alford’s often personal narratives, which she integrates into her textile masterworks. Alford has made small stitched items most of her life but she says it wasn’t until much later that she conceived of them as part of a larger whole—such as a quilt.

At times she uses images that are similar to one another, such as houses from the same neighborhood, or remembrances of a trip she’s taken; other times the images are more disparate.

Either way, unifying elements of color and texture render the work as a painterly, unified, cohesive composition. Quilts are her central work but Alford also creates sketches, collages, travel boxes, and postcard art. She collaborates on group projects and sometimes with just one other artist. Her work appeals on many levels, and the detail of her sewing, hand stitching, appliqué, collage, and other techniques enhance a narrative that is endlessly inventive.

Either way, unifying elements of color and texture render the work as a painterly, unified, cohesive composition. Quilts are her central work but Alford also creates sketches, collages, travel boxes, and postcard art. She collaborates on group projects and sometimes with just one other artist. Her work appeals on many levels, and the detail of her sewing, hand stitching, appliqué, collage, and other techniques enhance a narrative that is endlessly inventive.

An Artist in the Making

Alford is the third generation of her family in Grafton, but she was born in Texas in 1945 and grew up there. She studied fine arts in college but was concerned about making a living as an artist.

“Some of us didn’t believe we could support ourselves as artists,” Alford says, identifying a challenge common to artists and, it might be said, particularly to women artists.

So Alford went on to land a Master’s of Education in Special Education from the University of Arizona, and taught special education for 30 years. Retiring at 50, she returned to the idea of making art.

“All of a sudden I had the time and the interest,” Alford says, noting that the two don’t often coincide. “I’ve been taking classes and making art since.”

She also mentors artists, gathers groups, and explores opportunities around the world—as well as right in her own backyard in Grafton.

Her master’s degree led to an opportunity that reverberates to this day: After college she served in the Peace Corps as a rehabilitation volunteer, teaching blind students at the Cheongju Home and School for the Blind in Cheongju, Chungcheongbuk-do, South Korea.

“We went in as rehab and we were role modeling how to teach disabled people,” Alford says, “but we really needed to teach people English.” Teaching a language to the blind has unique challenges. “We’d do multisensory projects like cutting up an apple, cooking it, then eating it and talking about it.” Alford says she was able to draw on her art background to create effective activities for teaching students with various disabilities during her years in the classroom.

Travels with Frances

Alford became entranced with Korea. She recently made her sixth visit in 15 years there as an international guest artist invited to participate in a Bojagi Forum in Suwon, South Korea. Bojagi is one of Korea’s traditional fiber arts techniques. Artist Chunghie Lee founded The Bojagi Forum and organizes it annually. Lee met Alford on one of her trips to Seoul and invited her to participate in the 2016 Bojagi Forum. Lee is now adjunct at RISD six months a year and then six months in Korea.

Alford became entranced with Korea. She recently made her sixth visit in 15 years there as an international guest artist invited to participate in a Bojagi Forum in Suwon, South Korea. Bojagi is one of Korea’s traditional fiber arts techniques. Artist Chunghie Lee founded The Bojagi Forum and organizes it annually. Lee met Alford on one of her trips to Seoul and invited her to participate in the 2016 Bojagi Forum. Lee is now adjunct at RISD six months a year and then six months in Korea.

Alford travels extensively but not always in conjunction with a show. This past spring she went to Korea, stopping also in Thailand and Malaysia.

“I recognize [the ability to travel] as one of the blessings I have,” she says. Alford has also taken advantage of art history tours in Europe, where the history of a place is the backdrop for seeing art.

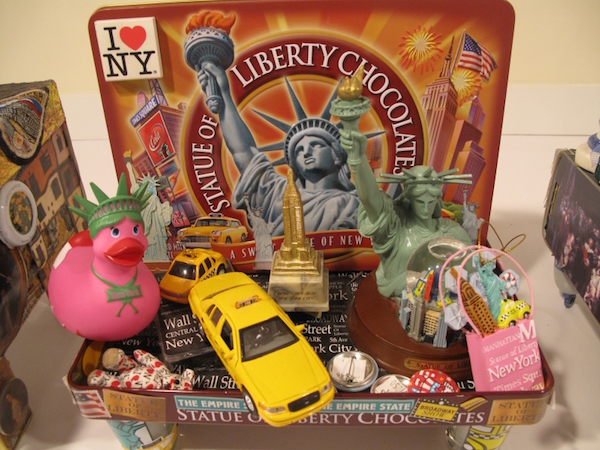

And Alford keeps busy on the road, bringing a sketchbook or small collages to work on. She also creates travel boxes on all of her trips: the kind of panoply of cultural references and travel ephemera that trigger memories of a journey. In France she bought a Babar lunchbox and incorporated a Claude Monet snow globe on top, a plastic figure of the Little Prince, a three-inch Eiffel Tower, and a magnet of a Van Gogh painting.

“While you’re in the middle of doing something serious, you can make something fun. I buy souvenirs and glue them in,” she says. She might also add museum tickets or postage stamps, and other small memorabilia into the 3-D collage. The back of the lunchbox is a postcard photo of the large clock from inside the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. It is a marvel of art and kitsch.

“At night in a hotel room I will work on it with my glue gun. Or I’ll work on one of my postcards. It might be 10 minutes a night or an hour a night,” Alford says.

Although she spends a tremendous amount of time on this not-so-serious work, Alford executes it with the same concern for composition she invests in her other work. At home she displays these like a travelogue. It captures Alford’s sense of whimsy and the fun of being an adult. Antonin Gaudi’s work graces her Barcelona box with images from La Sagrada Famìlia to the Park Güell, among others.

Although she spends a tremendous amount of time on this not-so-serious work, Alford executes it with the same concern for composition she invests in her other work. At home she displays these like a travelogue. It captures Alford’s sense of whimsy and the fun of being an adult. Antonin Gaudi’s work graces her Barcelona box with images from La Sagrada Famìlia to the Park Güell, among others.

“I get back home and work on my ‘real’ work, which brings up the question, What is the difference?”

Finding the Way

When Alford retired she began experimenting with different media and art forms, searching for what kind of work to make.

“The alchemy was the Internet, traditional quilting—and the artist in me. [Before then] I only knew about traditional quilting.” The Internet gave Alford access to contemporary projects, techniques, tools, conferences and a network of vendors and quilt makers.

“From the Internet I realized that there could be art quilting,” she explains.

Alford was living in Houston and began attending the International Quilt Festival in Houston, the world’s largest. The vendors, she says, have everything one can imagine in terms of materials, tools and equipment. “It was overwhelming” but also inspiring and energizing, she says.

It wasn’t long before she found the quilting community.

“I started working with a group of quilters and about six or seven of us who stuck with it became internationally known. It’s been a powerhouse of intelligent, creative women. Some of us came at it from science or math. One of the women who holds a Ph.D. in research science won a top prize in the quilt show in Houston. Another woman in the group was a geophysicist. “It was really interesting how, if we lined up that group’s work, each one of us has a completely different voice.”

“I started working with a group of quilters and about six or seven of us who stuck with it became internationally known. It’s been a powerhouse of intelligent, creative women. Some of us came at it from science or math. One of the women who holds a Ph.D. in research science won a top prize in the quilt show in Houston. Another woman in the group was a geophysicist. “It was really interesting how, if we lined up that group’s work, each one of us has a completely different voice.”

With Alford’s encouragement the group started creating group pieces, and despite her move to Vermont members continue to make group work—including some in the past three years.

“We’ll mail things back and forth. I’ve even flown to Austin to work on a piece. Cooperating somehow creates individual growth. I think the sum is greater than the parts in the group pieces we produced (contributions),” Alford notes.

“There is a section in the Houston show for group quilts. And I can say that it looks like one person pieced it, quilted it, embellished. Ours are more integrated,” she adds.

“So were started doing the group quilts and doing our own work along the way too. I had a weekly shot of energy because we’d meet once a week at my house. When I moved up here, I haven’t had much of that. I finally found a rug hooking group and they now come to my studio on Thursdays mornings. Rug hooking has a potato-chip quality to it where you can’t put it down. I do it when the group is here unless I’m working on a deadline and then I’ll do my quilting.”

She also gets together with the local postmistress, with whom she is contributing to an international project related to raising awareness of the Nazi regime’s attempted extermination of people with disabilities.

Art Imitates Life

What is noticeable right away is that Alford’s life is her art and her art is her life. She dresses stylishly, today in a dress with large white polka dots on a black background accentuating the black and white square floor tiles in her studio; her artwork is displayed organically in several locations inside the house; and her touch is subtly visible throughout her home, which she shares with Fritz Maassen.

A few years ago, she says, the two renovated their house down to the studs. The original house was built in the 1700s and the front part in the 1820s. Alford notes she and Maassen retained the character of the original home while opening it up and modernizing aspects of it for livability.

Various touches throughout the home highlight Alford’s attention to detail—and to tasteful fearlessness. She isn’t afraid to take risks to see what happens. A case in point? A playpen for her two Yorkies was created from a space under a staircase that, in most houses, would be walled off. Alford turned it into a whimsical pet palace. The comfortable nook has gone to the dogs while providing a safe den for them. It’s fully decorated—including a tiny chandelier and dog-sized couches, no less.

Alford’s studio makes use of the entire third floor, and there she imposes order on a riot of fabric, machines, beads, buttons, thread and sundry bits, necessary to the process. Alford works to maintain order with a system of shelving and colored drawers for fabrics, fabric bits and accessories. One wall is covered with a 70th birthday quilt in progress. Friends and acquaintances from around the world are sending in squares with Frances-related themes, some related to Korea, Texas, and Vermont. Framed postcard collages are everywhere. Her quilts are neatly stacked—a mile high, or so it seems. The woman is prolific.

Alford continues to pursue and enjoy activities in which she can teach and share her skills to interested fiber artists and art quilt enthusiasts.