By Meg Brazill

A visit to Mary Admasian’s studio is like chancing upon an archeological dig. A rectangular table runs the length of her studio. It is covered with a curious array of objects, from a neat stack of thin, flat stones to a pitcher of wild turkey feathers to handfuls of royal blue petals drying inside a clear bag. Small white shells nestle inside a pink lined box and a pair of rusty barbed-wire knots rests on a flowered takeout tray. Nearby, an aluminum pie plate—a palette of red, yellow and black paint—hints at the recent history of Admasian’s work in the studio. The materials are messy: they crumble, fade, and decay.

The studio is impeccable.

The great outdoors as pop-up studio

Admasian describes herself as “mostly multi-disciplinary” because she often works with a variety of media. The outdoors is her workshop of choice, so her studio, downstairs in her house, is largely devoted to preparing, organizing, and storing materials. Larger materials, such as branches, wire, and wood, are stored in the attached garage. It’s tempting to call her materials “ingredients” as there is a certain alchemy that occurs as she works with them.

“I primarily work outside,” Admasian says. “I call it my pop-up studio.” She and her husband, Peter Lind, live on a farm in East Montpelier with beautiful, long views. It’s easy to see the appeal of working outdoors, as well as the practicality of it.

“I like really strong natural light so I can see everything I’m creating. So much of my work is made from natural objects that there’s a lot of cutting, painting and drying. And a lot of building—I build inside and outside,” she explains.

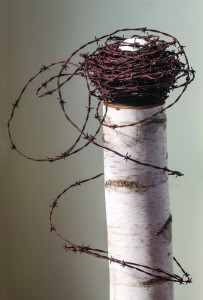

Admasian combs the fields and woods to source rocks, wood, bones, feathers, and butterflies. She scours flea markets and alerts friends as a secondary means of foraging. One notable exception to her use of natural materials is barbed wire, which is often found in the woods. Different gauges and strengths of the wire and different types and sizes of barbs make each kind unique. They’re made for different uses—meant to contain and protect, and often to assert, “Keep Out.”

“There’s an endless narrative to barbed wire,” Admasian says. “It provokes a lot of things for the people who engage with it.”

Barbed wire is difficult to handle and can quickly cause damage. “I wear heavy-duty gardening gloves and I have a code of how I handle the metal. If I’m careful of what I’m doing, I don’t get hurt,” Admasian says with the voice of experience.

Out of bounds and between the lines

In Mary Admasian’s new exhibition, “Boundaries, Balance and Confinement,” at the Brattleboro Museum & Arts Center (BMAC), she repurposes materials to create sculptures and assemblages that she says, “address how societal and psychological restraints both contain and free us.” Barbed wire plays a prominent role in this exhibit. Its duality is expressed through its constraining properties while also using it as a unifying metaphor throughout the exhibit.

Six works from her larger “Boundaries” series are on view. “Go Cut Yourself a Switch” (8-by-4-foot acrylic on board, 2014) is the largest piece on exhibit and, visually, the show’s focal point. Six bundles of five willow switches each are mounted vertically on a neutral-colored horizontal board and held in place with a short length of barbed wire. It is simple and breathtakingly beautiful.

The “switch” in the title refers to a short whip cut from a thin tree branch, typically a willow, that is used for corporal punishment. An adult might require that a child who is to be disciplined, go outdoors and cut her or his own switch, thereby inflicting psychological pain along with the physical.

“Boundaries” speaks to a light, beautiful, and empowering aesthetic that is uplifting while also presenting a more foreboding, rough-edged narrative. Viewers will no doubt bring a variety of perspectives to it.

David Schutz, the Vermont State Curator, describes “Boundaries” like this: “Encompassing elements of the Vermont vernacular, this work is beautiful, contemporary, and provocative, all at the same time.”

Hope beyond tears

Throughout the winter, Admasian worked on her newest sculpture, “Weighted Tears.” Created for the Brattleboro Museum & Arts Center, the sculpture will be on view through Oct. 8. The sculpture consists of five teardrop-shaped objects suspended from the eaves of the museum. Each object is made of aluminum rods, wire, and barbed wire, and is stabilized by a spherical weight. The smallest object has a light that will remain illuminated 24 hours a day.

The light, Admasian explains, may be perceived as an element of promise or a symbol of hope during difficult times.

Admasian is the recipient of a 2016/17 Vermont Community Foundation Grant, Arts Endowment Fund, for “Weighted Tears.”

A native of Detroit, Admasian studied at Eastern Michigan University and the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, before earning a BFA from Colby Sawyer College with honors in painting. She is the recipient of two fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center (Johnson, Vt.). Admasian’s work has been exhibited nationally and is in the collections of colleges, institutions, and private art collectors.

Admasian has worked as an artist, curator, marketing consultant, and creative director for the visual and performing arts. She has the rare talent of having an artistic sensibility in combination with a good measure of business acumen that she has put to service working for companies such as Ben & Jerry’s, where she was integral to building the brand. (Her husband was a flavor developer there and invented the cookie dough flavor and many others for them. Peter is currently in charge of innovation and new product development at Lake Champlain Chocolates.)

She has also created site-specific work and installations in collaboration with other artists, filmmakers, musicians, and writers. In the past year, she worked with multidisciplinary artist Kristen M. Watson to create an interactive body of work, “The SHE Project, Part I,” which explores what women of all ages experience as they cope with the pressure to maintain a youthful appearance at any cost.

Perhaps Admasian says it best: “Rusted objects have always been of interest to me—in particular, the connective yet alienating beauty of barbed wire. By prompting viewers to reflect on their individual interpretations of this collection, I hope to foster a deepening awareness of the issues surrounding boundaries and to stimulate conversations about breaking through them to effect social and personal change.”

There is no time like the present.

For more information, visit maryadmasianart.com.