A Bennington company lovingly produces felt dolls the old-fashioned way

By Bonnie J. Ross

R. John Wright was meeting up with his wife, Susan, to cast their votes for Jimmy Carter in the presidential election of 1976.

John, who had just lost his job at a hardware store in Brattleboro but who had spent several years becoming fascinated by the world of doll making, held something wrapped in a blanket.

“Want to see?” he asked Susan.

She peered down into the black button eyes of a crude doll hastily made from yellow flannel and sheep’s wool and stitched from her husband’s own imagination.

Little could the couple imagine that this first doll, comical and pale, would one day be insured for $1 million and occupy a crystal case in Japan, where it would be viewed by reverential doll collectors.

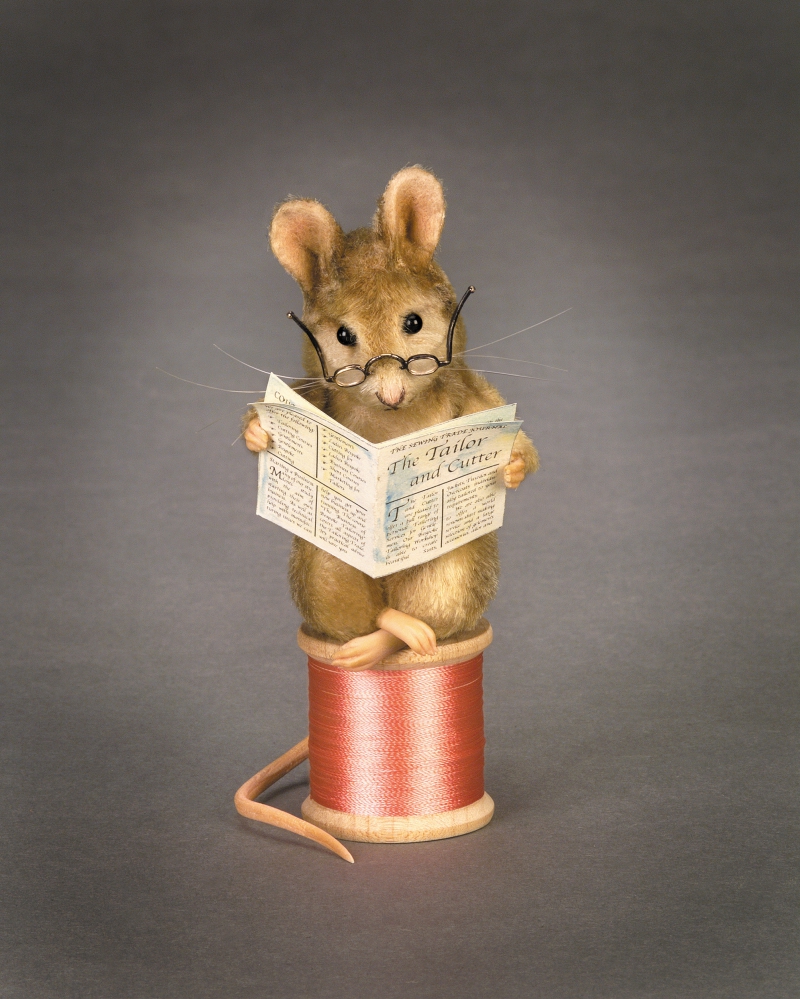

The Mouse Tailor, one of the characters from the Beatrix Potter children’s classic The Tailor of Gloucester. Only 585 pieces of this doll were produced in 2002.

The Wrights are now the president and vice president, respectively, of the R. John Wright Company, a collectible doll manufacturing company that is renowned worldwide and nestled in a little white house and brick schoolhouse building just outside of historic Old Bennington, where they have produced the limited editions of dolls since 2004.

There, the Wrights have translated their interest in the historic art form into a firm that has created more than 30 series of dolls inspired by the work of illustrators in classic children’s literature: think E. H. Shepard (Winnie-the-Pooh), Sir John Tenniel (Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland), and Beatrix Potter, creator of children’s books with charming drawings.

The company focuses on the intrinsic challenge of creating a well-known classic character in doll form, as if it stepped right off the page or screen.

But it’s not merely the dolls’ design that conjures another era. The company’s approach to dollmaking is something of a lost art, as Susan Wright points out.

Susan notes that the Wright doll company is the first modern producer of collectible dolls to use molded felt, the method used to make the comical German Steiff character dolls or sideways-gazing Italian Lenci dolls. Both styles of doll saw a peak in popularity during the 1910s and 1930s, respectively. In both cases, felt gave way to the more malleable vinyl or plastic.

Felt dolls are formed through a complex sequence of modeling and molding that begins in the R. John Wright Company’s second-floor design studio.

The studio is populated by Canadian author/illustrator Palmer Cox’s caricatural Brownies paper dolls; different stages of molded and cast doll arms, legs, and shoes; stuffed animals in various prototype stages; and a richly illustrated library of classic children’s books.

On a nicked and comfortably untidy worktable, John Wright uses a series of drawings to sculpt the initial clay prototypes of the dolls amid a collection of Beatrix Potter books and under the watch of several figures like of the character doll Woody from “Toy Story.”

The clay form of a curious monster, clearly recognizable as a wild and whimsical Maurice Sendak creature, lies in progress on the bench. A line of dolls based on Sendak’s classic 1963 children’s book Where the Wild Things Are will debut as one of the company’s next production series.

In a replication of the Bronze Age lost-wax method of sculpture, that clay model eventually is revealed in wax, which, in turn, is used to create a positive metal form that can then be used to create masks from buckram (starched and resined cotton fabric).

Felt is molded around the buckram forms and then stitched, stuffed, and finished with hand painting and small details such as fingernails (for The Wizard of Oz’s Wicked Witch of the West) or dozens of minute rivets (for the Tin Woodman).

It’s a complex process, but the resultant doll has a quality of warmth unique to felt, unlike the sterile quality of vinyl or the fragile, cold nature of porcelain.

All production is performed on-site with a dedicated team of artisans, many of whom have been with the company for decades. The company employs 45 people.

The Wrights personally design each prototype and oversee the production of the limited edition, ensuring that each piece is produced to the company’s exacting standards. Before leaving the workshop, every item is permanently hallmarked with a tiny “RJW” brass button, and John Wright signs every online order by hand.

In 2016, the company — which has come a long way from John Wright’s primitive, button-eyed flannel doll of the ’70s — will mark its 40th anniversary with joint ventures with Steiff, an extensive array of licensed pieces, and an infinitely creative, whimsical menagerie of mice, bears, cats, dogs, and lambs.

The Wrights have clearly shown that felt is up to the task of conveying the tender aura and delicate shading of Sister Maria Innocentia Hummel’s watercolors or the nostalgic whimsy of Shepard’s beloved renditions of Piglet and Pooh. They feel a connection in both the form and structure of the figures that have provided a successful career for the couple.

The dolls might hark back to another era, but, as Susan Wright notes, “the past is our future.”

To learn more about the company, visit http://www.rjohnwright.com. The company offers its “First-Ever” RJW Studio Open House on Feb. 12 and 13, 2016.