Preserving the Past: “Meeting at Fay’s Tavern (Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, Bennington, June 1791) (detail),” 1938. Leroy Williams, (1878-1965). Oil on canvas, 25 x 35.25 inches.

The days were dark as the Stock Market Crash of 1929 took its toll on the country in the early 1930s. Crash to Creativity: The New Deal in Vermont, on view at Bennington Museum through Nov. 4, sheds light on this vital state history, focusing on the role of these many government-sponsored New Deal projects.

The exhibition features photography, paintings, prints of post office murals, and architectural drafts that were sponsored through the government’s New Deal programs. Powerful examples of Regionalist and Social Realist paintings include Francis Colburn’s “Charley Smith and His Barn” and Ronald Slayton’s quietly optimistic “The Planter.” Also on view: furniture from Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) cabins, and letters and audio transcripts of Vermonters from Federal Writers Project archives.

Bennington Museum Executive Director Robert Wolterstorff explains that Vermont’s culture has long been shaped by an interdependent relationship between traditional values and progressive ideals.

Preserving the Past

Having sustained moderate economic hardship since the mid-19th century, the Green Mountain State could not afford further losses. Despite a tradition of local pride and stubborn independence, the effects of the Depression opened Vermont to many aspects of Roosevelt’s liberal New Deal, Wolterstorff says.

Building the Future: “Social Security,” 1947. Francis Colburn (1909-1984). Oil on canvas, 42 x 36 inches. Collection of Vermont Historical Society, Gift of Ruth P. Bogorad, Shelburne, Vt.

Many of the projects created through the New Deal helped to solidify stories passed down from one generation of Vermonters to the next, such as the Battle of Bennington and the Green Mountains Boys. Bennington Museum collaborated with a handful of artists through the state’s Federal Art Project (FAP) to create large murals and easel paintings documenting local historical events and people of note. These images, carefully researched, create a cohesive, arguably whitewashed picture of Vermont’s past.

For Jamie Franklin, curator of Bennington Museum, a few of these projects told lesser-known aspects of the state’s history.

“They challenged the wisdom that was passed down through the generations and added a layer of complexity to Vermont’s cultural landscape—such as the mural and easel painting of the Rev. Lemuel Haynes commissioned by the Bennington Museum,” Franklin says.

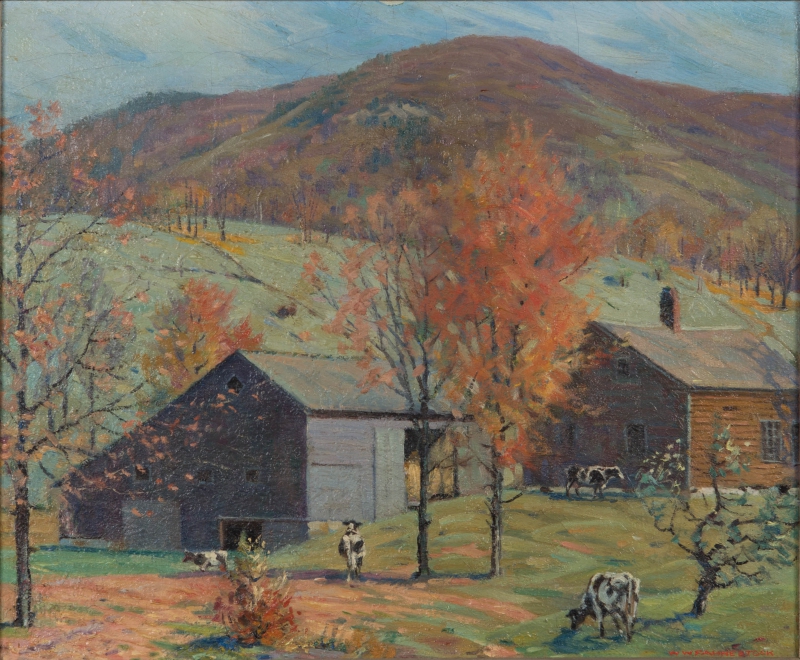

Inventing the Present: “Vermont Idyll,” 1938. Wallace Weir Fahnestock (1877-1962). Oil on canvas, 20 in. x 24 in. Collection of Bennington Museum.

Haynes, explains Franklin, was the first black man to be ordained as a minister in America.

“He had a long career preaching to largely white congregations in his home towns of West Rutland, Vermont, and adjacent Granville, New York, and the surrounding region from 1788 to 1831.It is the preservation of both histories—the widely viewed and the less known—that created the true history of Vermont,” Franklin says.

Inventing the Present

He says that as a whole, from easel paintings and prints to photographs and post office murals, the creative output of the New Deal in Vermont “helped to crystalize the traditional marketing and tourist image of Vermont as picturesque old time New England.”

The most commonly explored themes range from agricultural production—including haying and dairy farming—and maple sugaring; marble and granite quarrying; and the budding recreation industry, notably skiing. This idealized image of Vermont was and is a staple of the state’s tourism marketing.

However, such artists as Francis Colburn and Ronald Slayton, two of the most significant native Vermont artists to participate in the Works Progress Administration’s FAP produced visual works notable for their powerful sense of place and willingness to address difficult social issues. Much of their work was in line with the Regionalist subject matter popular with many artists working through the FAP, depicting common Vermont people and landscapes.

On the other hand, some of their work, especially Slayton in his painting “Unemployed” and suite of three woodcuts—“Clearing the Fields,” “Fuel,” and “Social Activities of the 1930s”—tackled dire economic, political, and social problems Vermonters faced in the Depression.

“Both artists depicted hard-working Vermonters, farmers, quarry men, factory workers and their families, with dignity and respect. In paintings such as Colburn’s ‘Charley Smith and his Barn,’ ‘Granite Quarry,’ and ‘Family Group,’ and Slayton’s ‘Mowing Away,’ ‘Hired Man,’ and ‘Burlington Gothic,’ both artists make their humanist desire for better working and living conditions for their fellow Vermonters an overriding theme of their work,” Franklin says.

The Federal Writer’s Project (FWP), one of the five major work relief programs the WPA sponsored, employed more than 6,000 writers and is best remembered for the American Guide Series. Every major city and town in all then-48 states plus Alaska and Puerto Rico was documented. The format included essays on state history and culture, descriptions of major cities, automobile tours of important attractions, and photographs.

Franklin explains that in addition to the guidebooks, FWP authors conducted extensive interviews with locals that were typical to a city or region. These were used to draft insightful, deeply personal narratives. These went largely unpublished during the run of the FWP; they’re preserved at the Library of Congress and are excerpted throughout the exhibition.

Building the Future

The CCC was created under 1933’s Emergency Work Act, under which thousands of young men were recruited to plant forests, create parks, build roads, erect dams, and pursue other conservation activities. Vermont boasted one of the earliest and most productive of the nation’s CCC projects as the state was prepared with public lands and development projects for the 40,800 men assigned to its CCC camps. Since 1909 the state had acquired thousands of acres for forests and parks but by 1933 had been able to develop only two picnic areas.

Most of the buildings erected for the state park system with CCC labor utilized readily accessible local materials, including rough-hewn logs and stone. David Fried, who trained at Cornell University’s School of Architecture and graduated in 1933, spent his first few years out of school designing rustic buildings in Vermont and New Hampshire for the National Park Service, Franklin says.

“He was one of the few known architects of these buildings that injected a modernist sensibility to his work. The lodge at Mount Mansfield is one of his distinctive buildings that blend rustic and modern design,” he adds.

The CCC also played a significant role in the birth and early development of Vermont’s ski industry. Perry Merrill, state CCC director and commissioner of the Vermont Forestry Service, saw the potential for winter recreation in the state forests if a network of ski trails could be built. One of the most impressive undertakings was the work done on Mt. Mansfield, now Stowe Mountain Resort. Here, trails, lifts, a base house, and other elements of the infrastructure were built. Some of the architectural renderings and early photos documenting this project are on view in Crash to Creativity: The New Deal in Vermont.

The CCC also had a hand in the ski facilities now operating on Bromley, Okemo, and Burke mountains, as well as defunct areas in St. Albans and Shrewsbury. A large part of the state’s infrastructure was built in this way.

The bottom line: Unleashed by the New Deal, the creative and innovative work of artists, architects, writers, construction workers, and civil employees helped restore American confidence and prosperity when this was sorely needed, and these voices live on. Check it out.

For more information, visit http://www.benningtonmuseum.org.