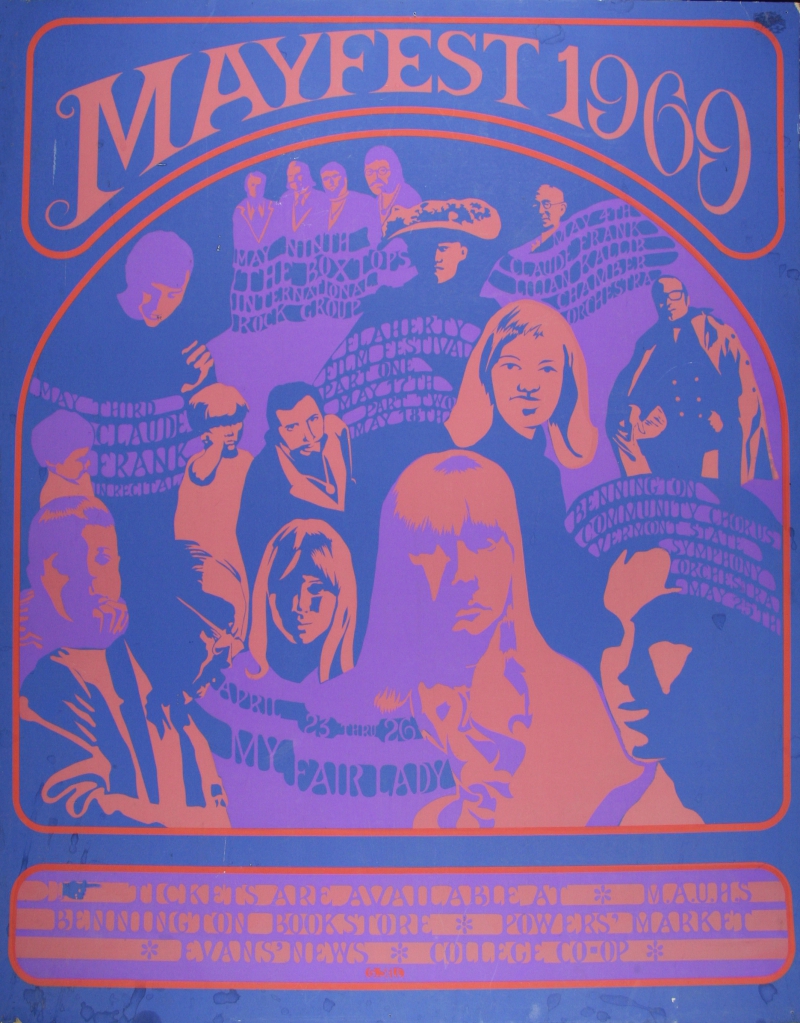

Mayfest Poster, 1969. George W. Sell (dates unknown); silkscreen on paperboard, 27.5 x 21.625 inches.

By Yvonne Daley

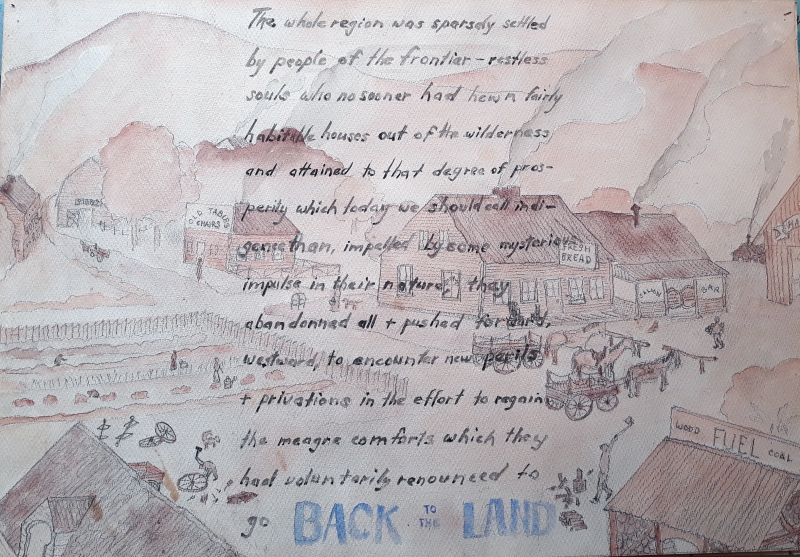

Arguably no state was more greatly influenced by the counterculture than Vermont as tens of thousands of young people loosely associated with the movement moved to Vermont during the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s, eventually blending into communities small and large, both embracing the local culture and impacting it with their ideas and ideals.

Young Man Holding a Peace Candle at Vietnam Moratorium Rally, Bennington, 1969. Greg Guma (b. 1947).

In acknowledging that phenomenon, the Bennington Museum’s dual exhibits Fields of Change: 1960s Vermont and Color Fields: 1960s Bennington Modernism, present the national movement in local context through photography, puppetry, clothing, art, and text.

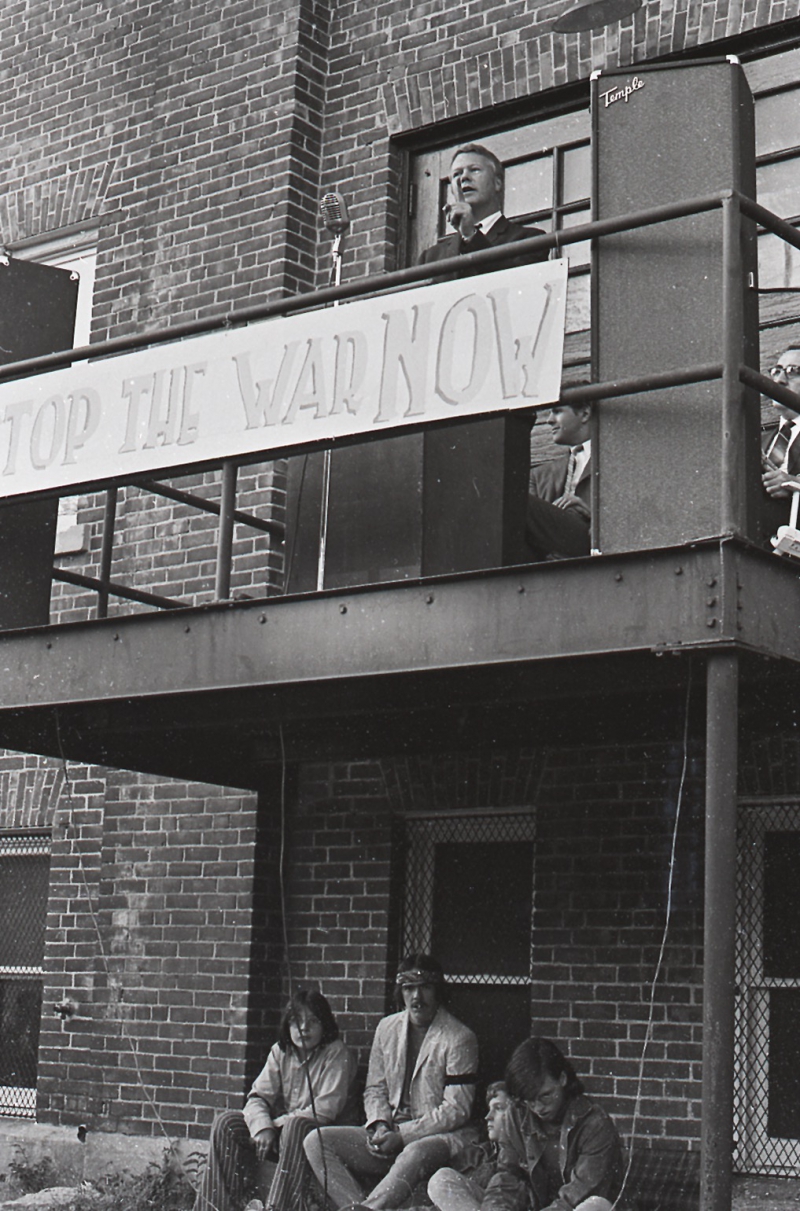

The exhibit opens with journalist and author Greg Guma’s photograph of the late Gov. Philip Hoff, the first Democrat elected to the state’s highest office in more than 100 years. Coming to office in 1963, Hoff brought dramatic changes to the rural state, changes that helped attract the young people to Vermont. Along with its natural beauty, cheap housing and small population, exiles from the anti-war movement were drawn to a state where the governor spoke of the need for integration between whites and blacks, and later supported the peace candidate for the 1968 presidential election, Eugene McCarthy. One of Guma’s photographs shows Hoff speaking at the Bennington Armory in favor of the nationwide Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam.

Perhaps the most remarkable document on display is a transcript of a letter published in the Bennington Banner on April 12, 1968. Written by local residents, it begins, “We Are White People,” and laments the treatment of black people brought by the writers’ ancestors to America. The writers acknowledge “the virus of racial prejudice in all of us” and confess ignorance in knowing what to do to redeem past and future wrongs. Among the signatories are Gloria Gil, one of the founders of the pottery cooperative, Bennington Potters; William B. Abernathy, then the pastor of the North Bennington Congregational Church; and Edward J. Bloustein, then president of Bennington College.

Although the epicenters of the counterculture movement were located in and around Brattleboro and Plainfield and throughout Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, the Bennington area boasted its own artists, artisans, photographers, clothing designers and political activists whose work brought the larger story to the local arena, sometimes resulting in opposition. The exhibit includes Guma’s 1970 photograph of a school board feud over a poster advertising the production of the play Brecht on Brecht. After much local protest, police removed the poster under the premise that the use of the American flag in an advertisement was illegal. This was the first in a series of moves that led to conservatives gaining control of the local school board and the removal of what they considered overly progressive policies and curriculum from Mount Anthony Union High School.

Former Governor Phil Hoff Speaking at Vietnam Moratorium Rally, Bennington, Vermont, 1969. Greg Guma (b. 1947).

Nonetheless, as the exhibit illustrates, a bustling cultural scene developed in Bennington that featured a monthlong celebration of the performing arts called Mayfest, showcasing music, visual arts and films by local educators, musicians and documentarians.

In Vermont as elsewhere, members of the counterculture illustrated their world and wore decorative clothing. The exhibit includes clothing sold at The Gingerbread House and the Upstreet Boutique, once owned by fabric designer Tzaims Luksus, whose designs became favorites of the more progressive residents.

One highlight of the exhibit included a reading and discussion of the impact of the counterculture on Vermont with three Vermont authors, poet Verandah Porche of Guilford; memoirist Tom Fels of Bennington; and nonfiction author Yvonne Daley of Rutland. In introducing her reading, Porche used the words Pariahs to Pillars of the Community, cleverly summarizing how the young people who were once considered suspect were exactly what Vermont needed in the 1960s, much as young people are needed today, as Vermont has become again one of the oldest states by population age in the nation.

Like Porche, many of the transplants who came to Vermont have long become essential members of Vermont’s arts, business and political fields. Indeed, those members of the commune Total Loss Farm, which Porche and her friends made famous in their books 50 years ago, now serve as members of their town’s Selectboards, on library and cemetery committees, and in the Vermont legislature while their books, art, music and community efforts contribute to the vivacity of the state, north and south, east and west – and beyond.

Bennington Museum, at 5 Main St. (Route 9), Bennington, is open daily June through October.